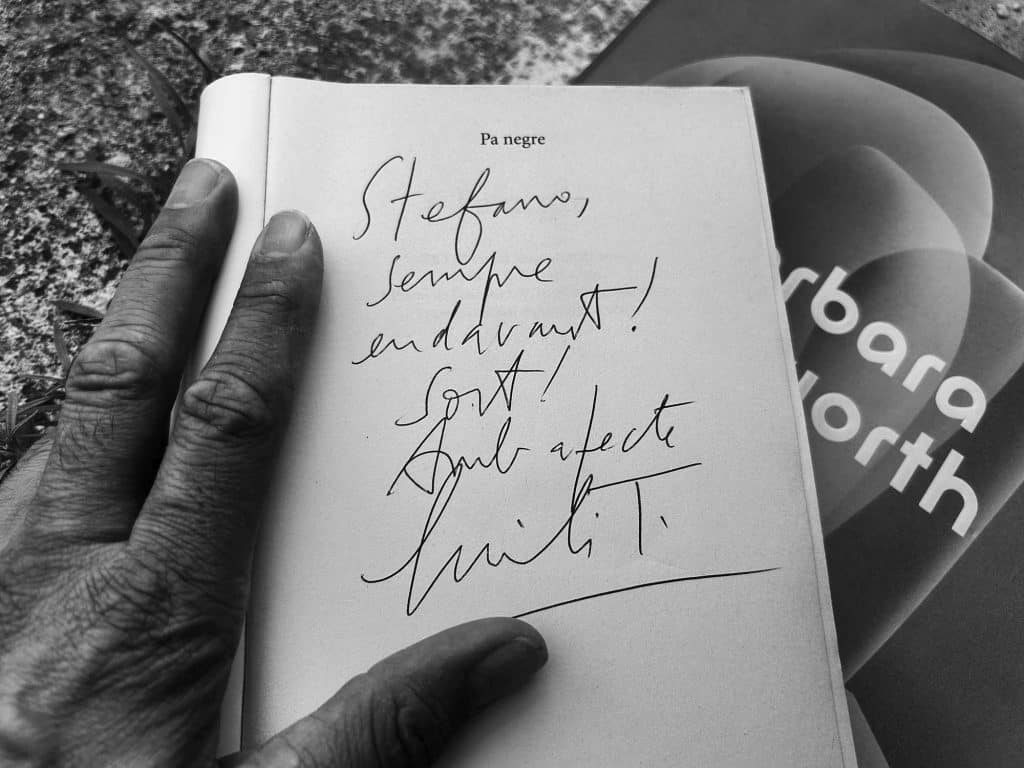

When you land in Barcelona as a young newcomer, seeking new life and fresh possibilities, and you’re lucky enough to meet a writer like Emili Teixidor (1932–2012), everything changes. The eager visitor may pass through without seeing the city. But meeting him throws you into Catalan history. After that, the people, the neighborhoods, and even the streets speak differently to you.

Our choice of Carrer Margarit 30 was never random. It became the root of our project, the well we keep drawing meaning from. The building has been recently listed as a Bé Cultural d’Interès Local (local cultural heritage) by the Generalitat. But for us —who aimed to restore it as a living part of the neighborhood— it is more than a protected site. It’s a body alive with voices, laughter, passions, and secrets of past generations—memories we gathered during our few tea sessions with Emili.

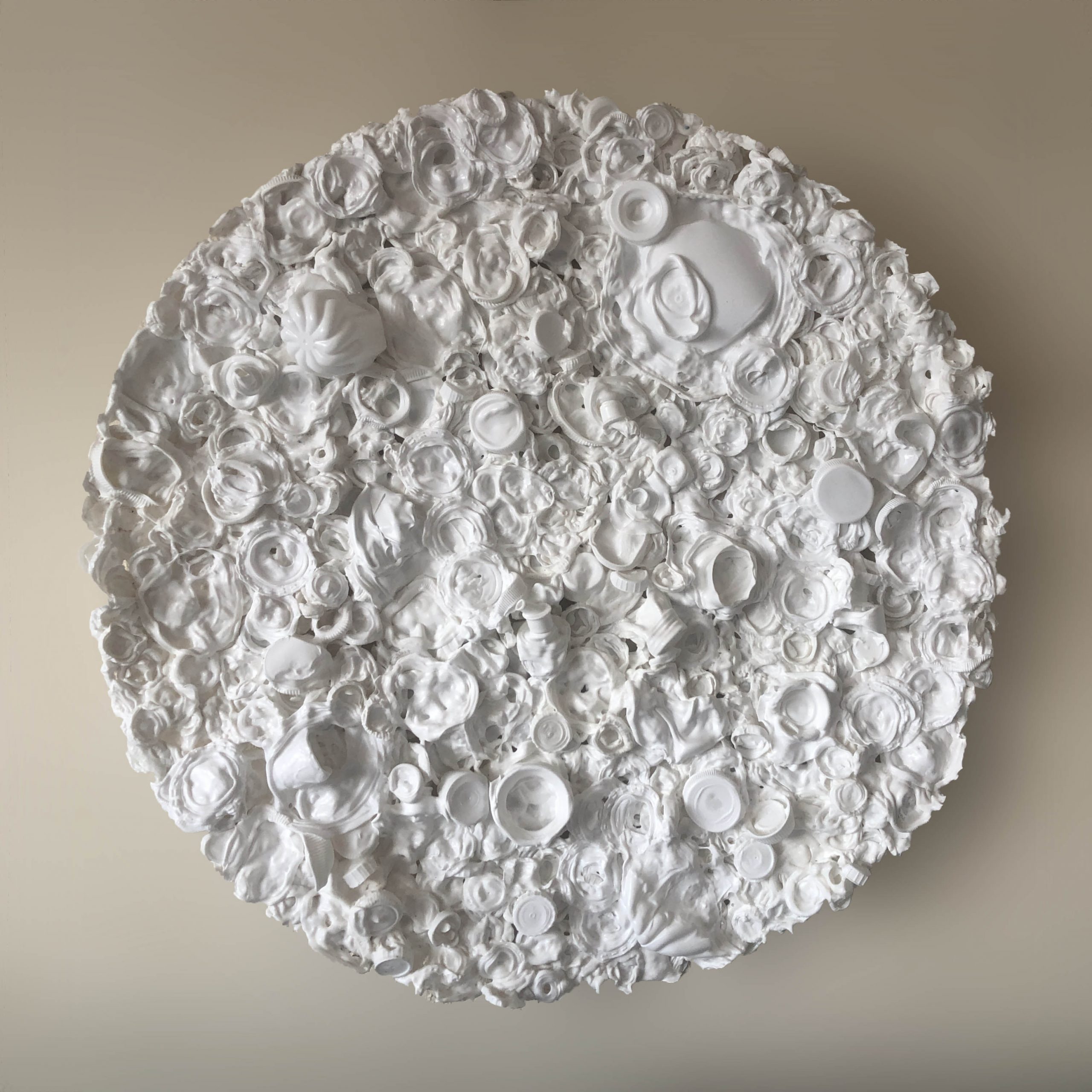

This Modernisme (Catalan Modernism) little masterpiece, designed by Antonio Facerias around 1905, stands between two party walls. It spans a ground floor, five upper floors, attics, and a rooftop terrace. The ground floor is striking: three animal relief panels: a dragon, a monkey wearing a hat (our “mono”, monkey in Spanish), and an eagle—set among vegetal sgrafitti. A false-quoin frame encases the facade.

Floors above open into balconies with ornate iron railings, supported on the first floor by conspicuous corbels. Their details—pilasters topped with animal-decorated capitals, vegetal reliefs, and green-and-yellow floral motifs—carry the spirit of Catalan modernism in full bloom. Tall semicolumns on the fifth floor rest on plant-like corbels, echoing the decorative language seen elsewhere in the neighborhood.

It has long been whispered in the neighborhood that the building was never meant as a conventional family home. Among the last long-time residents, stories circulated—remarkably consistent with each other—that Margarit 30 once housed women kept under the protection of a well known Barcelona family of doctors. According to these accounts, the young women lived here in comfort and discretion, meant to entertain the heirs of the dynasty. Such arrangements, they explained, were not unusual in those years and formed part of a hidden yet widely recognized social fabric across Poble-sec. Many homes there were built this way, weaving a hidden yet visible social fabric.

I recall the words of Mrs. P. (2025), who was born in the building and is now a friend:

“As little girls we couldn’t grasp why grandmother said those walls had witnessed more secret loves than prayers…Rooms made for elegant silence, not family dinners…her voice would drop, but her eyes glowed with complicity.”

Mrs. C. (2025), also raised in the building, and friend as well remembered:

“On the landing you’d hear multiple languages, laughter, song snippets rehearsed endlessly. A neighbor, a graceful entreneuse, hosted musicians nightly. After their shows at El Molino or the Apolo, they’d come celebrate here. My mother claimed those rooms were livelier than the stage.”

Both women insisted on anonymity. They feared that descendants of the original owners might still live nearby, and they didn’t want their memories to stir trouble.

That golden age of Paral·lel—the main avenue cutting through Poble-sec—remains little known to outsiders. Once lined with theaters, cabarets, and operetta halls, it was dubbed the “little European Broadway” in the early 20th century. A remarkable exhibition at the CCCB in 2013, which I was lucky enough to visit, brought it back to life with posters, stage sets, and rare documents. Much of that belle époque atmosphere has vanished, though a few historic theaters still stand today.

Downstairs, the building atmosphere was different. A small carpentry workshop occupied the ground floor for decades. Sawdust, horses, even a dairy cow; this was practical, hard-working life nestled beneath decades of glamour.

Walking along Carrer Margarit today, echoes of the past reappear in subtle ways. Recent plaster removal revealed faded signage of a former corner inn, one of the many places once famed for champagne, imported wines, and liqueurs; like the walls themselves deciding to speak again. This glorious era of the surrounding areas has been beautifully narrated.

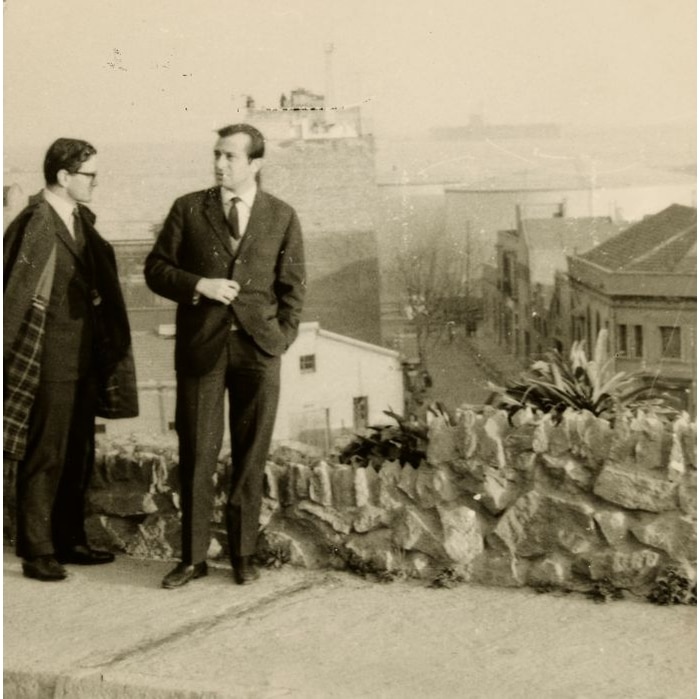

Even Pier Paolo Pasolini passed through here. In 1963, the Italian man of letters, theater, and cinema, always close to working-class neighborhoods, strolled these streets and Montjuïc’s gardens. We can only imagine what living memories he gathered during his brief visit.

So, Margarit 30 is not merely a building. It bears silent witness to secret loves, glittering nights, artisans at work, and childhoods shaped by the scent of wood and distant operetta arias. Every balcony, every window still holds a fragment of that life.

In the few encounters I had with him, Emili told me —not sadly, but with dignity and clarity— how the city was already being overtaken by the destruction of memory. We can’t know if our project would have pleased him—but we like to think it would have.

This is our little space on Carrer Margarit: a house of memory, restored to life, once again part of the neighborhood’s peculiar story.

Stefano Vuga, curator, mono30